Can our delta cope with the drought?

We spend millions on protecting the country against flooding, and we're now suddenly faced with one of the driest summers ever recorded. Is our water management adequately prepared?

It would seem so. So far, the victims of the drought are water animals in dried out streams and ditches, shrivelled crops and bushes, and the occasional company that is no longer permitted to discharge warm water. Society is not suffering and the taps are still freely open, reassured director-general Michèle Blom of the Department of Public Works on 2 August following the weekly meeting of the National Water Crisis team. However, extra work is required to limit the damage: that means keeping drying dikes wet, deploying extra pumps and watering crops.

It's not really surprising how little we are troubled by the drought: we live in a delta of one of Europe's largest rivers after all. So where are things going wrong, if at all? Are the farmers and their withered corn the victims? Will the cows go hungry for grass next winter? Will the price of potatoes go up? Or is it all still manageable as long as we have drinking water and there is no hosepipe ban?

Drinking water is not a problem

On a monthly basis, we jointly use approximately 100 million m3 of drinking water. Even during this drought, the Rhine still transports 1000 m3 per second into the Netherlands, which translates into more than a month's drinking water per day of Rhine discharge. What's more, most of our drinking water comes from the groundwater, which can pretty easily cope with a few months' drought: groundwater is a large-scale buffer and does not readily evaporate underground.

Rivers and IJsselmeer supply enough water

And so the Rhine supplies enough water for purposes other than drinking water, and the IJsselmeer and Markermeer lakes jointly provide a massive water buffer: each centimetre of water they contain is good for 14 million m3 litres. So plenty of water. This stock of water is therefore freely available to help supplement drier areas.

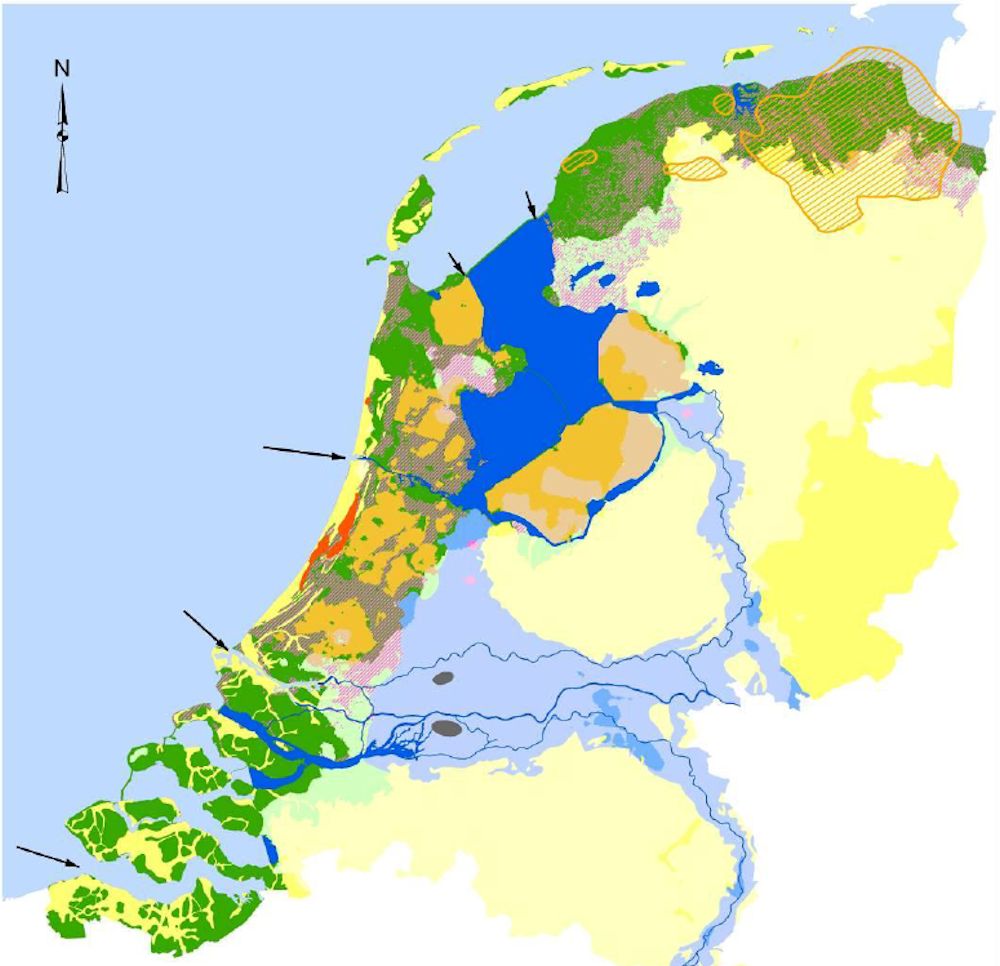

Buffer serves no purpose for sandy area

Yet there is a problem: some parts of the country cannot benefit from the water buffer, particularly the higher-lying sandy areas in the eastern and southern Netherlands. There are no canals or large pipelines there to enable supply of water from elsewhere. These regions are therefore completely dependent on rainwater and the groundwater level. In some of these areas, agricultural land may no longer be irrigated by pumping water from ditches. In others, a similar prohibition applies to the groundwater, particularly in nature areas which might suffer permanent damage due to drought. Check out the map below, showing the Twente Achterhoek region for example, one of the driest in the country.

Problem of dry sandy area is not new

The fact that dry sandy soils are sensitive to drought is old news: the same problem occurred during the previous dry summers of 1962, 1976 and 2003. Ideas have been proffered to solve the issue. There was the bufferboeren project: ensure a higher groundwater level on farming land, introduce extra organic matter into the soil so it retains water more effectively, and grow crops or species of corn which root more deeply and are therefore less sensitive to drought. Until now, such measures have never progressed beyond the pilot stage, and are only applied to a limited extent. Farmers and water boards will therefore need to take a more active approach.

Salt is the stealthy enemy

Another problem in times of drought is salt. Salinisation is an issue all along the coast. This is partially due to freshwater and salt water coming into contact, resulting in salinisation of the freshwater. The most extreme case is found at the Nieuwe Waterweg where the silty seawater enters the Netherlands freely. When Rhine levels are high, the average annual flow of the river is 2200 m3/s, the salt has little chance, and is not problematic. However, when the flow is halved as is currently the case (though still 1000 m3/s), the influx of the salt reaches much further.

The situation in the North Sea Canal is slightly different again. Although there are sluice gates at IJmuiden, salt water is let in with each passage.

Equally important is the saline seepage which permeates the soil from the North Sea. The islands in Zeeland are particularly prone to this, but so too is the Haarlemmermeer lake and the Friesian-Groningen region along the Wadden Sea.

Tackling the salt through freshwater flushing

Until now, we have mainly combated the salt by flushing freshwater through the soil, ditches and waterways. The Zeeland region has a special agricultural water pipeline for that purpose, which taps water from the freshwater basins in the Biesbosch area.

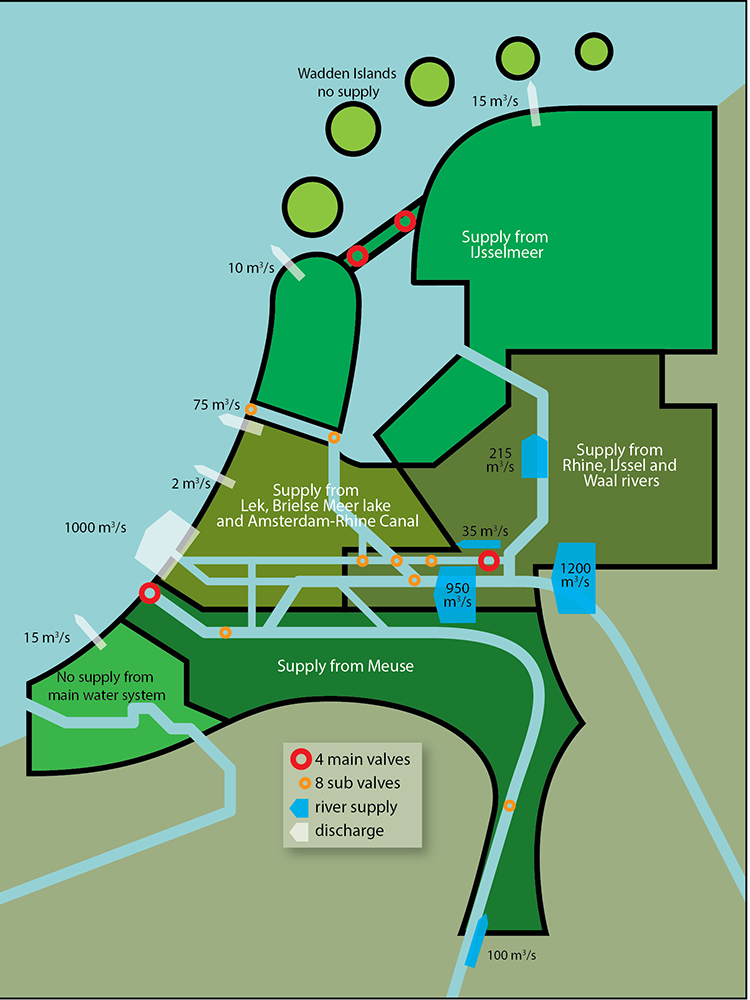

The special supply of freshwater to Gouda is iconic for 'the battle against salinisation'. Normally, that water is extracted from the Hollandse IJssel river, a branch of the Rhine whose water is destined for agriculture, for example tree nurseries in Boskoop, and for the Nieuwkoopse Plassen nature area. However, the reduced Rhine flow has resulted in salinisation of the Hollandse IJssel, and forced Gouda to source its water via an alternative route. It now comes from the Amsterdam-Rhine Canal and the Lek river, for which a special water supply system has been established, see the map below.

The lion's share of freshwater goes to the Nieuwe Waterweg

On looking at the map of our freshwater system, it is immediately clear that most of the supply of freshwater is used to flush the Nieuwe Waterweg:

The numbers speak for themselves. A freshwater supply of 200 to 300 m3/s is sufficient for drinking water, keeping the groundwater at a workable level and preventing salinisation. However, we require 1000 m3/s to combat the encroaching salt via the Nieuwe Waterweg, which is more than is currently supplied by the Rhine. This is why the salt is also advancing via the Nieuwe Waterweg. The volume of Rhine water currently used to hold off the salt in the Nieuwe Waterweg is not available for other purposes.

The normal status of our water management is: pump fresh out as quick as possible

Water management in the Netherlands is mainly determined by one principle: water must be discharged as quickly as possible. We canalised the rivers for that purpose, while pumps keep the low-lying Netherlands dry. Day in day out, we dispatch immense volumes of water into the sea. If we were not to do so, large parts of the Netherlands would be underwater.

We do not have buffers, and do not need them as long as the rivers continue to supply water and there is a sufficient volume in the large freshwater basins. But what if they no longer suffice? And how realistic is that risk? During an all-time low in 1911, the flow rate of the Rhine was still 789 m3/s into the Netherlands. If we were more capable of predicting drought, we could opt to store extra freshwater during winter and spring, by temporarily raising ditch water levels, for example. However, we fail to do so, as we take a reactive approach to the situation.

Drought is an unknown factor in our water management

As a country, the Netherlands is very wasteful with freshwater. And that's not a problem, as long as the Rhine continues to supply it at Lobith. That tap too is still open. Only if that begins to falter, do we need to structurally take a long hard look at ways of retaining the freshwater for longer, rather than mainly discharging it into the sea as we do now. (Frank Biesboer)

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!

Opening photo: Archive image Department of Public Works

Meer artikelen

Een AI-fabriek in Groningen

Gezondheid meten via zweetdruppels

Nieuwste artikelen

Een AI-fabriek in Groningen